Radio counterintelligence during WWII is a topic of great interest to me, not only for the historical relevance, but also for the modern-day relevance. While it might almost seem unbelievable, shortwave (and likely amateur radio) are still being used to pass secret communications, particularly with the proliferation of digital modes available to the average user. This also means monitoring capabilities are greater than ever, and they begin to rival what governments have had for a long time. The ability to record wide swaths of frequencies for later analysis is a major move forward, and I can only imagine what those early radio counterintelligence operators would have been able to accomplish with the same abilities!

August 2017 marks the 72nd year since the close of WWII, and I thought it might be useful to look back to some of these operations as a reminder of the power of radio, and as a reminder of its potential use today.

During the 70th anniversary of D-Day several years ago, some stories surfaced of long-held secrets from WWII’s battle for information. As a member of the Radio Society of Great Britain (RSGB) I get their monthly journal (excellent, by the way!) and I regularly peruse their bookstore for interesting entries. In addition to the usual radio-related offerings, there are often articles and publications focused on the clandestine aspects of the war effort, particularly about communications.

Likewise, I occasionally listen to 1940s U.K. Radio which features both war music of the era and special programming from that time, as well as radio announcements and news broadcasts from the war. These are actual news and public service announcement recordings which were played over the air. They are all interesting in one way or another, but one in particular has stayed with me regarding the enlistment of help from teenagers to monitor shortwave radio broadcasts for Axis communications. The age requirement was 12 years old and up. Hearing the public service announcement as it was broadcast back then was a real thrill!

While broadcast radio certainly played a major role in the war effort, the shortwave monitoring and counterintelligence maneuvers were vital to the success of the war effort. Shortwave radio also played a key role in finding out about casualty lists, as civilian shortwave monitors notified families of captured U.S. military personnel concerning their status as prisoners of war during World War II. (There is an interesting book devoted to those letters compiled by Lisa Spahr entitled Radio Heroes: Letters of Compassion.)

Centers of Operation  There were numerous centers of operation for communication gathering during WWII around the world, but three stand out in particular, one in England and two in the United States, in part because of the mystery surrounding them. Bletchley Park is the most famous in Buckinghamshire, England, established in 1938 as a code-breaking center and training facility. While the code-breaking was done at Bletchley Park, listening stations were set up in other locations so as not to draw attention to the building, particularly regarding air attacks.

There were numerous centers of operation for communication gathering during WWII around the world, but three stand out in particular, one in England and two in the United States, in part because of the mystery surrounding them. Bletchley Park is the most famous in Buckinghamshire, England, established in 1938 as a code-breaking center and training facility. While the code-breaking was done at Bletchley Park, listening stations were set up in other locations so as not to draw attention to the building, particularly regarding air attacks.

While most famously known for breaking the Enigma code, an even more significant achievement was the breaking of the teletype code known as the Lorenz Cipher. The Lorenz cipher was broken without ever having captured one of the teletype machines used to produce the code (see image below). The cipher was broken due to German operator error.

The code was designed so the machine would operate based on a codebook of 100 possible cylinder settings, after which a new codebook would be used. The sequences were never to be repeated to ensure they were one-time ciphers, the hardest of all to break. As it turned out early on in August of 1941, a message of some 4,000 characters was sent which was received incorrectly because of an improper machine setting. The receiving station requested a resend (the request being sent in the clear, no less!), which allowed cryptologists to have two versions of the text using the same machine settings, but with slight alterations such as abbreviations, which made the second text shorter.

With the two transmissions to compare, known to cryptanalysts as a depth, the cryptanalyst Brigadier John Tiltman sorted out the two plaintexts allowing him to figure out the keystream (HQIBPEXEZMUG). Even with the keystream it was not until three months later that another cryptologist (Bill Tutte) analyzing the text identified a 41-character pattern which allowed the whole machine to be reverse-engineered.

Decryption machines were then built which aided in copying messages, with varying success rates, but a lot of human intervention was still required.

An original Lorenz machine located at the Bletchley Park museum

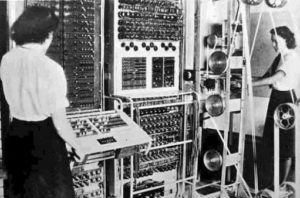

Toward the end of the war a machine known as the Colossus was built which was much more robust, and a true forerunner to more modern computers.

The machine was programmed through plugboards and jumper cables, and generated the cipher keys electronically. This meant it took less time to set the decryption machines up compared to the earlier Lorenz replicas. The machine used an optical reader which read at 5000 characters per second, meaning the tape travelled at almost 30 miles per hour! By the final stages of the war there were ten of these machines in operation, but most were dismantled at the end of the war on orders of Winston Churchill.

Ultra

The Lorenz cipher and Enigma, as well as other such high-level decryption work were classified as Ultra. Ultra was the designation adopted by British military intelligence in June 1941 for wartime signals intelligence obtained by breaking high-level encrypted enemy radio and teleprinter communications at the Government Code and Cypher School (GC&CS) at Bletchley Park. This was used to provide a higher level of intelligence importance than the Most Secret level, which had been considered the highest. This designation was also adopted by Western Allies for their highest-level intelligence

A Colossus Machine (curtesy of the U. K. Archives)

The decryptions which came from both the Lorenz and the Enigma codes were always classified Ultra, and like the breaking of the Lorenz cipher, operator error was responsible for much of the success in cracking the Enigma code. Much of the credit for breaking the Enigma code goes to the Polish Cipher Bureau which first broke the code in 1932. By the outbreak of WWII, the Enigma machines were made far more complex, but because of the earlier work of the Polish group the Allies were able to ramp up their decryption abilities to keep pace. The Poles provided reconstructed Enigma machines and decryption techniques to the British and French in 1939.

The German Army, Navy, Air Force, Nazi party, Gestapo and German diplomats used several variants of the Enigma machines. During the earliest stages of the war the Germans used landlines for much of the planning and coordination, but later moved more and more to radio communications. Interestingly enough it was the German Air Force whose somewhat sloppy transmission practices allowed the earliest and best opportunities to break the Enigma code.

After the war, it was found out through interviewing German cryptologists/operators that they believed the Enigma machines were just too complicated to break for the Allies to spend much effort trying to decrypt the messages. Fortunately, they were wrong.

The information gleaned from the intercepts were distributed in various ways after being cleared through Bletchley Park. The communications element of each SLU (Special Liaison Unit) was called a “Special Communications Unit” or SCU. These were highly mobile, often in cars, and capable of getting Ultra information out quickly. Radio transmissions were encoded using one-time cipher pads. A commander in the field receiving Ultra intelligence was fed a cover story crediting a non-Ultra source, including at times fake scouting missions which were intentionally visible to the enemy. They were sent to “discover” German positions already known from Ultra intelligence gathering.

In some cases, the intelligence was so sensitive it was impossible to act on it at all because to do so might reveal to the enemy their communications had been penetrated. Information did not just come from listening and communication centers connected with Bletchley Park, however, as there were numerous “Voluntary Interceptor” posts throughout the country, some 1500 radio listeners. They were listening for any useful transmissions, particularly Enigma transmissions. This small “army” of listening recruits provided valuable information as well as redundancy confirmation of transmissions, as more than one operator was likely to hear any given transmission. The Express and Star publication ran a very interesting story on one of these Voluntary Interceptor stations which may be found here:

Next time around I will explore some of America’s contributions to radio monitoring during the war.

73, Robert AK3Q

Originally published in the May 2017 issue of the Q-Fiver.